Living with thyroid eye disease: Veronica’s story

Living with thyroid eye disease: Veronica’s story

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a rare and unsightly eye condition with few treatment options. Veronica shares how she has lived with TED for over 20 years.

by Rosemary Ainley, 22 January 2025

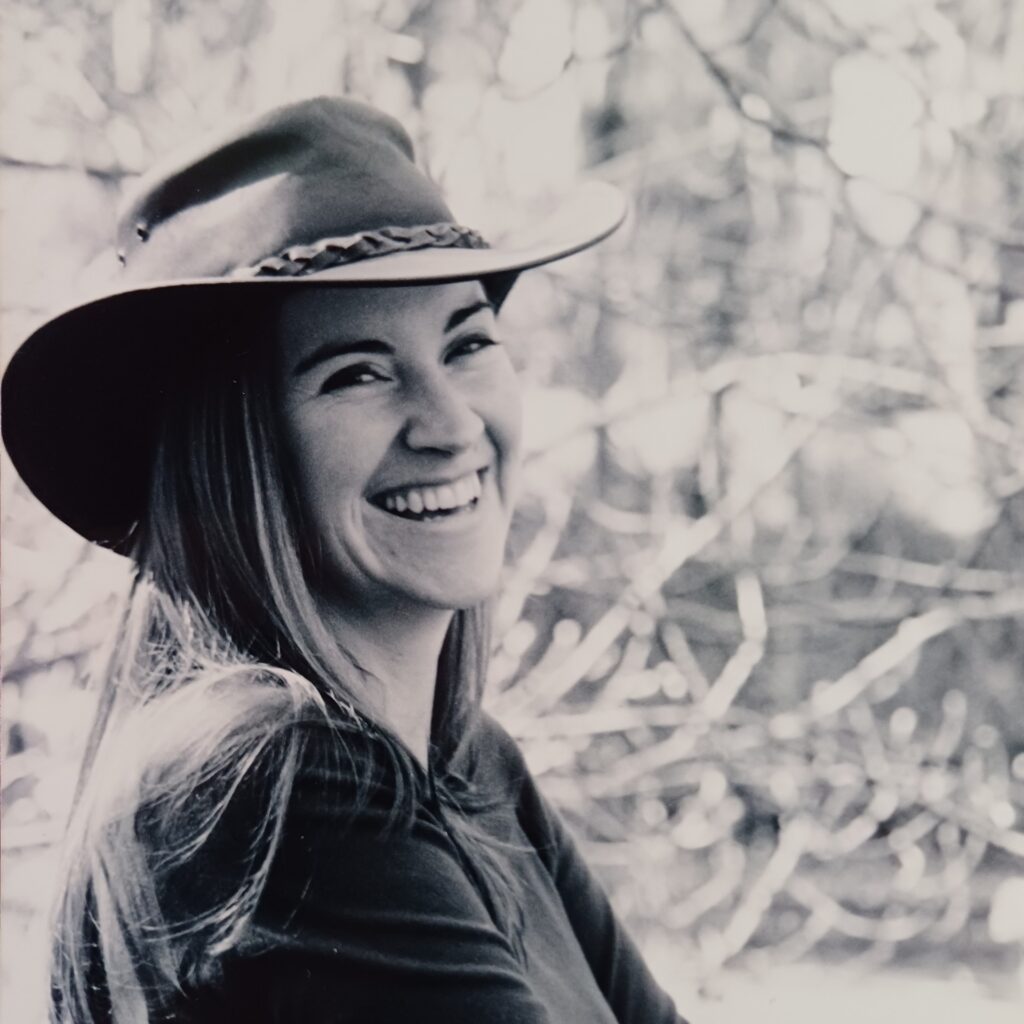

Veronica in late 2003, 3 months pregnant, before she was diagnosed with TED.

Veronica one day after giving birth, showing significant bulging of her eye.

In the early 2000s, Veronica had a good life in Adelaide with her husband and two young stepdaughters while working with people with disability. By 2004, Veronica was in the third trimester of her first pregnancy when her husband noticed her left eye was open while she was asleep.

“I started getting a gritty, sandy feeling in that eye and it looked like it was bulging and staring a little”, said Veronica (now 51).

Her pregnancy was already complicated. She became very unwell at 20 weeks gestation with a kidney stone that moved and got stuck, resulting in a severe infection. Then, following surgery to insert a stent to drain her kidney and feeling unwell from the pregnancy and antibiotics, Veronica saw her GP about her eye issues.

She hadn’t seen that GP before, so she brought photos to show him how her eyes previously looked. Luckily for Veronica, that GP had an interest in endocrinology (the field of medicine related to hormone issues) and he quickly suspected Veronica could have thyroid eye disease (also called Graves’ ophthalmology, Graves’ orbitopathy or Grave’s eye disease).

Veronica’s thyroid eye disease journey begins

At that point, Veronica’s thyroid levels were normal, so she didn’t have Graves’ disease or Hashimoto’s disease. She was referred to an endocrinologist (a specialist in hormonal disorders) with expertise in such conditions during pregnancy, who confirmed her diagnosis. She also saw an ophthalmologist (a specialist in eye disorders) with expertise in thyroid eye disease (TED).

As there were plenty of specialists in Adelaide, Veronica had appointments within weeks of her symptoms appearing. No medical treatment options were available then, so the ophthalmologist monitored her symptoms, and Veronica did her best to manage them with non-medical treatments, such as eye drops.

Other symptoms she experienced included pain, grittiness, watery eyes and intolerance of bright light.

About thyroid eye disease

- Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a little-known autoimmune condition that causes inflammation and damage to the fatty tissues, connective tissues and muscles around the eyes. It has no known specific cause, but many factors can play a role.

- The thyroid gland (located in the neck) produces hormones that affect many organs in the body (including the eyes).

- Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s disease are autoimmune conditions that affect the thyroid gland and are closely associated with TED. Graves’ disease can cause an excess production of thyroid hormones (hyperthyroidism). Hashimoto’s disease can cause an underproduction of thyroid hormones (hypothyroidism). Both conditions can be fatal if left untreated.

- While rare, TED can also be diagnosed in patients with normal thyroid function.

- TED usually affects both eyes but can affect just one. Symptoms vary from person to person and from mild to severe.

- Pressure from inflammation behind the eyes can push them forward, which gives a bulging appearance (proptosis). This can make it hard for the eyelids to close and cause pain, misaligned eyes and double vision.

- Other symptoms can include redness, puffiness, dryness, a gritty feeling, watery eyes and light sensitivity.

- TED is generally mild and may resolve itself over time. More severe cases can cause significant discomfort and eye damage.

- TED starts with an active and inflammatory stage lasting approximately six months to three years. During this stage, symptoms can come and go.

- Once symptoms stabilise or stop, TED switches to an inactive phase. In this phase, some people may not experience any symptoms. However, that does not mean the disease has gone away. Also, some people may need treatment or surgery for damage caused by prolonged inflammation.

- TED is not contagious so it can’t be transmitted. TED has no cure, but pain and inflammation can be managed through limited treatment options or surgery.

(See our Thyroid Eye Disease Education and Resource Hub for more details about TED and how to live with it.)

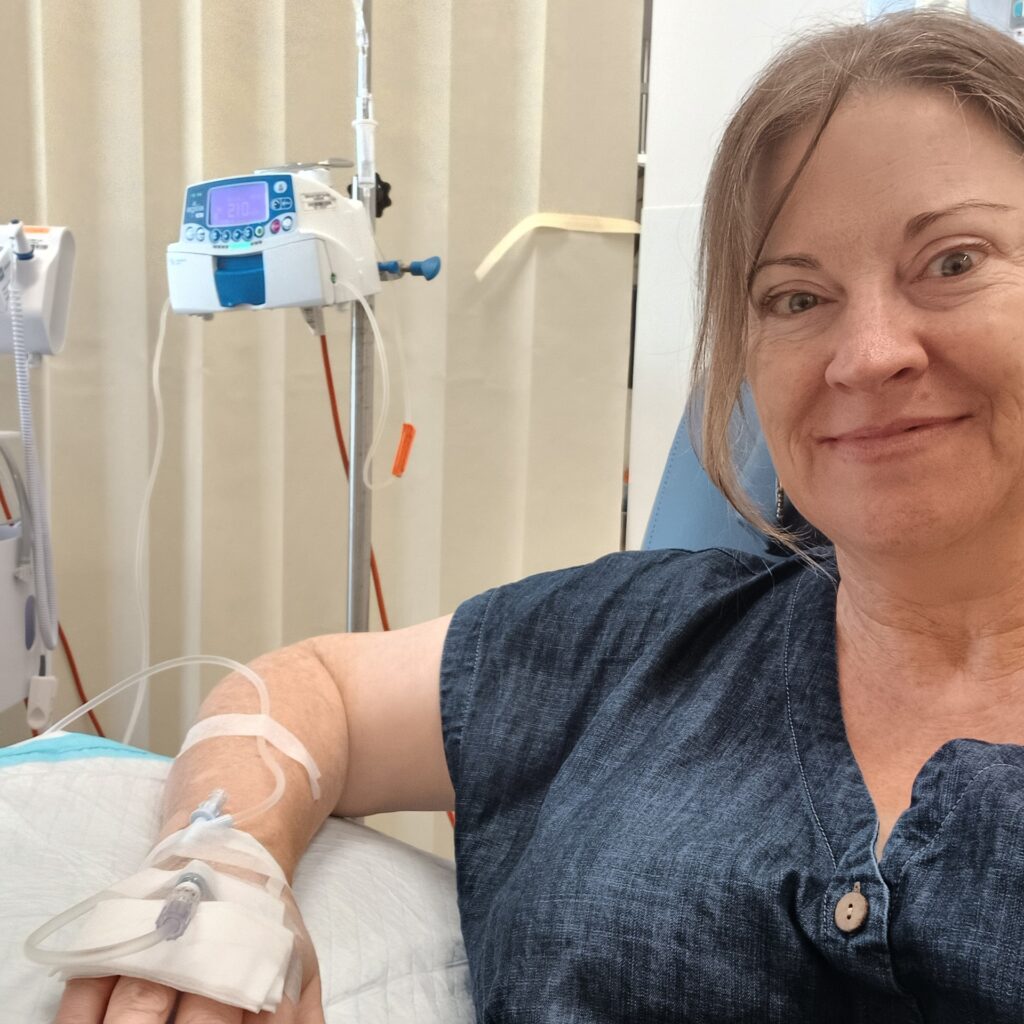

Veronica having her IV steroid infusion in December 2024.

‘Red face Wednesday’, a term Veronica uses the day after her weekly IV steroid treatment.

Managing TED symptoms without medication

Although Veronica had another autoimmune condition called vitiligo (which causes the pigment in the skin to change colour), those symptoms were relatively mild and didn’t concern her greatly. She already followed sun-smart practices for her vitiligo so she continued those. She also used cold compresses and rested her eyes as much as possible to help with her TED symptoms.

Veronica found the visibility of her symptoms, alongside the changes in her body during her pregnancy, quite distressing. “I was very conscious that I looked different and worried people would look at me and not understand what was happening with my eye. When I went to the ophthalmologist for the first time and saw people like me in the waiting room, it was comforting and reassuring to know this was happening to other people”, she said.

At that time, online information about her condition was minimal, so Veronica relied on her specialists to guide her. She was aware there was a risk that, if the disease got worse, she could face surgery to release the pressure behind her eye. Such pressure could compress her optic nerve and affect her vision. However, she decided to deal with things as they arose and focused on getting through her pregnancy.

Grave’s disease and remission

Veronica’s bulging eye got much worse during labour as that process puts a lot of pressure on the whole body, including the brain. This took some time to settle down.

Around six weeks after her first son was born, tests showed Veronica’s thyroid was overactive and she was diagnosed with Graves’ disease. She started medication for that condition and her specialists monitored her closely. Then, after around 18 months, her Graves’ disease went into remission so she stopped her medication.

At the same time, her TED went from the active to the inactive stage and her symptoms reduced dramatically. However, she continues to have a flare on her upper eyelid to this day.

A new state but familiar symptoms

By 2010, Veronica and her family lived in a small regional town in New South Wales. Aware her conditions could return, Veronica asked for regular blood tests to check her thyroid hormone levels. That year, her results confirmed her Graves’ disease had returned. Luckily, this was picked up quickly so she went straight back on medication. She also knew what to do to manage her symptoms.

She was then offered two additional treatment options for her Graves’ disease — to have surgery to remove her thyroid or to swallow a radioactive iodine drink to reduce her thyroid levels. One of the risks of thyroid surgery is damage to the vocal cord nerve. It also leaves a large scar across the neck. Also, TED can continue even after thyroid removal. Radioactive iodine can aggravate pre-existing TED.

Veronica opted not to do either and continued her existing treatment. The gamble paid off in her case as, after around six years, her Graves’ disease went into remission again, and this time without a flare-up of active TED.

Veronica’s conditions return

In December 2023, Veronica noticed her heart was doing about 100 beats per minute while resting. She suspected her Graves’ disease had returned. Tests confirmed this so she restarted medication.

Yet, accessing the care she needed was challenging. “Many Australian regional towns have doctor shortages and it can take weeks to get an appointment,” she said. She managed to get some basic care via telehealth appointments with city-based doctors and ordered her prescriptions online. However, she couldn’t get regular blood tests to monitor the effectiveness of her medications and doses.

It was five months before she could get another GP appointment in person. By that stage, she was exhausted and experiencing a lot of brain fog (cloudy thinking). That doctor wasn’t experienced in endocrine conditions and didn’t realise her thyroid had become underactive. That was picked up months later when she finally saw an endocrinologist in Melbourne (via telehealth), who reduced her medication.

Then, around May 2024, Veronica noticed tiny fluid bubbles on her eyeballs but they weren’t painful. Her eyes also started to feel gritty so she wondered if her TED was returning.

At Veronica’s next eye check-up, the optometrist dismissed her symptoms as dry eyes (a common symptom of Graves’ disease). Although still worried, Veronica took his advice and continued to use eye drops and monitor her symptoms. Then, around July, Veronica started experiencing double vision, restricted eye movement when looking up, stabbing eye pain in the morning, eye fatigue plus puffy and red eyes and eyelids.

Immediately concerned, she tried to get the specialist support she needed, but once again, being in a regional area made getting such access a long and complex process. In the meantime, she saw another optometrist who took her symptoms seriously. Veronica then had an appointment in Sydney a few weeks later with an ophthalmologist specialising in TED. He confirmed her TED had returned and arranged for her to have an MRI scan. The scan showed the muscles behind her eyes were very inflamed, indicating that Veronica’s disease was severe and needed urgent medical intervention.

More treatment options to consider

Veronica read up on the latest TED treatments and learned of a medicine (tepotumumab) being used in the US to treat the condition itself rather than just the symptoms.

She asked her ophthalmologist about it and learned it was being trialled in Australia.* In rare cases, that medication can affect the hearing. Veronica had some residual hearing loss from a childhood illness so she was excluded from that study.**

Instead, Veronica was advised to try steroid treatment, intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP), to reduce the inflammation in her body as a whole. That involved her travelling to a Sydney hospital for a series of 12 weekly infusions. She also had to seriously consider the possible side effects of prolonged steroid use (such as osteoporosis, diabetes, increased blood pressure or gastric ulcers).

At the same time, Veronica needed to start an immunotherapy drug to calm her immune system and complement the effects of the IVMP. However, immunotherapy also increases the risk of infections and skin cancer.

“I had to think about what’s worse, the current situation or what might happen in the future,” said Veronica. “It felt like a gamble, but I had to trust my team, find a balance, go step by step and focus on what I could control”.

“It was important for me to take the lead in negotiating with my endocrinologist and ophthalmologist about my treatment plan and asking many assertive questions like, ‘I’ve heard about this’ or ‘Can you tell me about this?’ Gathering information so I felt confident I was making the best decision,” she said.

“There was an option to do nothing, but the risk with untreated serious thyroid eye disease is that the muscle compresses the optic nerve, causing vision loss or blindness. It can’t be treated if it gets to that stage and it was certainly not something I wanted to face,” she continued.

Veronica started taking vitamin D and selenium to help guard against the potential side effects of IVMP, along with other medications prescribed by her endocrinologist to prevent unwanted side effects. She was already attending yoga classes to help lower her inflammation and cortisol (stress hormone) levels. Her doctors also monitored her blood pressure, blood sugar levels and other blood tests to see how her body handled her medications.

Veronica’s TED journey continues

At the time of writing, Veronica was nine weeks into her IVMP treatment course and, by six weeks, she had already had a one-millimetre reduction in the proptosis of her eye. “That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it is a lot when it’s your eyes. And so it was pretty exciting to have that result at six weeks,” she said.

Other improvements included reduced stabbing eye pain and less sensitivity to glare. She is managing a roller coaster of side effects from IVMP, including having trouble sleeping, increased fatigue, mood changes, digestive upsets and having a red, flushed face the day after her infusion (likely from increased blood pressure).

The hope is Veronica’s eyes will continue to improve over the following months. She will stay on the immunotherapy drug for some time to maintain any gains from the IVMP infusions. Ideally, she will go back into remission within the next year. However, “Because the thyroid eye disease doesn’t always follow the same path as Graves’, there’s no guarantee that if I go into remission with Graves’, the eye disease will stop,” she said.

After that, Veronica and her ophthalmologist will know if she will need surgery to correct her eye or eyelid positions. “I’ll just focus on my wellbeing and recovery and keep a positive approach to life and then see what happens,” she said. “What I would love is for my eyes to return to normal and the disease never to return but I’ve heard it was rare to get it in the first place, certainly during pregnancy, and it’s even rarer to get it multiple times so I don’t want to be that person.”

The stigma of invisible TED symptoms

While TED hasn’t affected Veronica’s eye’s ability to see, her symptoms squeeze her eyeball, which changes the shape of her eye, causing double vision. That makes reading things such as supermarket shelf signage hard for her.

“I have to tip my head right up because my eyes won’t move up. I look at people at odd angles. Sometimes, I have to look out one side to see people. They think I’m giving them a side eye or looking over their shoulder but I’m trying to look at them,” said Veronica.

Veronica has also avoided going out. Partly to reduce her risk of picking up a contagious infection (as her immune system is compromised), partly to avoid the glare of the summer sunshine and partly so she doesn’t have to explain her health issues to others.

Currently, Veronica says that although her right eye feels worse, both eyes look similar and she doesn’t have the striking stare some people with TED have. “People can’t see what I’ve got unless they look closely. Then they’ll see the puffiness or blistering on the eyeballs but a lot of it isn’t visible”, she said.

Veronica has mixed feelings about having mostly invisible symptoms. “People don’t need to know my health business. But at the same time, when it comes to taking time off work — I’m in a small town — if I go out and people see me, they’ll wonder why I’m not at work”, she said. “I don’t want to have to explain myself but I might need their help because my vision’s been affected”.

Advocating for care

Veronica’s children no longer live at home so her husband and some close friends are her main sources of support. She now works as a domestic violence specialist, so her work is quite stressful. However, she hasn’t been able to maintain employment as her eye symptoms make it hard to look at a computer screen for long periods or conduct home safety assessments, which is part of the role.

Driving has also been challenging for her. Although legally able to drive, she has lost her confidence and now mainly relies on her husband or the limited public transport options to get around. “Having to consciously move my eyes to try and focus on something takes a lot of energy. And while I’m doing it, I’m not blinking much, which dries my eyes,” she said.

Travelling to Sydney for her half-hour infusion takes five and a half hours on a bus and then taking local trains in Sydney. Not to mention an overnight stay and returning home the next day. “All I wanted to do was get there, get it done and get home. I had very little energy for anything else,” said Veronica.

Of course, Veronica wanted her treatment done locally. She successfully advocated for four of her 12 treatments at her local hospital, saving her a lot of time, energy and money.

Reframing her limitations

Veronica has spent the last two years studying photography and she was worried her eye disease would affect her ability to continue taking photos. “But someone recently said to me, very wise fellow, that you can let your limitation be your inspiration. And if the limitation for me is my photos are a bit blurry, well, that’s going to be the result of my eye disease and that’s okay”, she said.

“It just so happens that blurry photos are on trend now. So maybe it’s a good time to have thyroid eye disease”, she concluded.

* Tepotumumab is currently being considered for use in Australia by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee and the Therapeutic Goods Administration. See the Advocacy section of our Thyroid Eye Disease Education and Resources Hub for more information about this process.

** If tepotumumab does become available in Australia, Veronica would still prefer not to take that risk until there are further studies about how significant the risk of further hearing loss is. However, she believes it could benefit many people with TED.

This Post Has 0 Comments